The takeover of Kabul by Taliban fighters was planned over many months. First, they took most of the border crossings between Afghanistan and its neighbours, Pakistan and Iran. Then they took the larger district capitals, followed by Kandahar and finally, the capital Kabul.

The border crossings gave the Taliban an important source of revenue, after they replaced the lawful government's officials and started to exact transit fees for every car, good or person crossing the border. This was a heavy blow for the Afghan government, since 50 per cent of the country's paltry revenues came from custom duties.

The other important source of income was and remains trafficking in drugs, mainly cocaine and heroin, going through Iran to the West. According to Afghan government estimates, poppy-growing areas increased by more than 37 per cent in 2020. In 1996, the year the Taliban took over the country after a long and bloody civil war, they worked to reduce the growing of poppies based on religious reasons, but they soon recognised the extent of the losses to themselves and to the rural population, which lives off this trade. Afghanistan quickly returned to being the world's largest exporter of drugs.

As long as the legitimate government was in place, it enjoyed immense foreign aid, estimated at comprising 80 per cent of its annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP), thought to be $20 billion. This aid funded the government's budget. In its first years, right after the country was conquered by an international coalition in 2001, donor countries mobilised to rebuild the country. The tens of thousands of soldiers who streamed into the country also played their part in driving the economy, bringing with them foreign investors, aid and welfare organisations, as well as contractors and service providers. The latter quickly learned the rules of deep corruption, which lined their pockets with hundreds of millions of dollars.

In November 2020, the donor states committed to giving the government $12 billion between 2021 and 2024. The American administration alone allocated $3.5 billion for military and civilian aid. The government budget included $295 million in aid to small and midsize businesses, which would create 1.9 million jobs. Donors and international financial institutions knew that a great portion of their aid ended up in private and political pockets, not in the projects it was intended for.

$500 MILLION FOR JUNK: It's enough to view the latest report by the office monitoring the rehabilitation of Afghanistan on behalf of the U.S., disseminated at the end of July, in order to understand the depth and extent of corruption and theft in this country. In one instance, the U.S. paid $547 million for the purchase of 20 refurbished transport planes for the Afghan army.

The planes arrived in an unusable condition; the refurbishing was poorly done and did not meet any safety standards. A few years later, 16 of these planes were sold for $40,000 and converted into scrap metal. According to the report, $8 billion were paid since 2008 to civilian authorities for construction and the acquisition of vehicles, but only $1.2 billion of these ultimately reached their destination. There is no information regarding the rest of this money.

The report can also partly explain the failing of the Afghan army in its efforts to halt the Taliban takeover. There are 320,000 soldiers in the rosters of the army, but estimates are that only 280,000 soldiers were actually in service. The rest are "ghost" soldiers, reported by their commanders in order to pocket the salaries of these fictitious soldiers. Now, these funds, which drove the country's economy, will also disappear.

Foreign aid groups have left or will soon leave the country. Foreign forces were reduced even before that, and their contribution to the Afghan economy gradually evaporated. The deep unemployment is expected to grow when the Taliban forbid women to work outside their homes. Although women comprised only 16 per cent of the labour force in recent years, that was enough to change societal customs and rules, creating hope that over time their participation in the economy would grow.

In the festering swamp of corruption, the government did manage to expand education and health networks, even allocating significant budgets toward these purposes. Success was partial, with half the male population remaining illiterate, and a much higher rate among women. But families were not forbidden to send their sons and daughters to school as was the case during the Taliban rule, and as is expected to happen now. Health services received a lot of funding on paper. From time to time there were reports about the inauguration of another hospital or clinic, which soon turned out to be just a collection of unfinished structures with no personnel or equipment. Estimates are that 78 per cent of payments for education come from the private pockets of citizens, not from the state budget.

THE WEST'S DILEMMA: With the collapse of the Afghan government and the rise of the Taliban regime, the issue of financing and managing the country's civilian systems has been brought into sharper focus. The Taliban is inheriting a poor and miserable country, with many regions still lacking regular water supplies or functional health services. But under the ground lie some real treasures. Geologists and researchers working for the U.S. army conducted a survey in 2010 and estimated the value of the country's resources at more than a trillion dollars. These are currently estimated at $3 trillion.

Among other resources there are iron ores worth more than half a billion dollars, copper, niobium, cobalt and a precious lithium. The demand for this element, used in car batteries, computers, cellular phones and more, has spiked by more than 20 per cent in recent years, with prices rising accordingly. A Pentagon report from a few years ago labelled Afghanistan the "Saudi Arabia of lithium."

While the world is concerned about the flooding of Western markets with opium, cocaine and heroin made in Afghanistan, China, Russia and Pakistan have already started weaving their ties with Taliban leaders, with their eyes set on mining these resources. For China, Afghanistan is a strategic transit point for its Belt and Road initiative. But while a war was raging between the Taliban and the country's legal government, China refrained from developing a mining and extraction industry of these resources.

The expected brutal treatment of the country's civilians by the Taliban does not particularly worry China or Russia. The security the Taliban can grant their investments is the factor that could now entice these investors. It's not just China, Russia and Pakistan that are eyeing the bounty lying beneath Afghanistan. The European Union's foreign secretary hurried to clarify last week that "the Taliban won the war and we'll have to talk to them." Talk about what? Human rights? A more moderate interpretation of Islam? Or about economic cooperation?

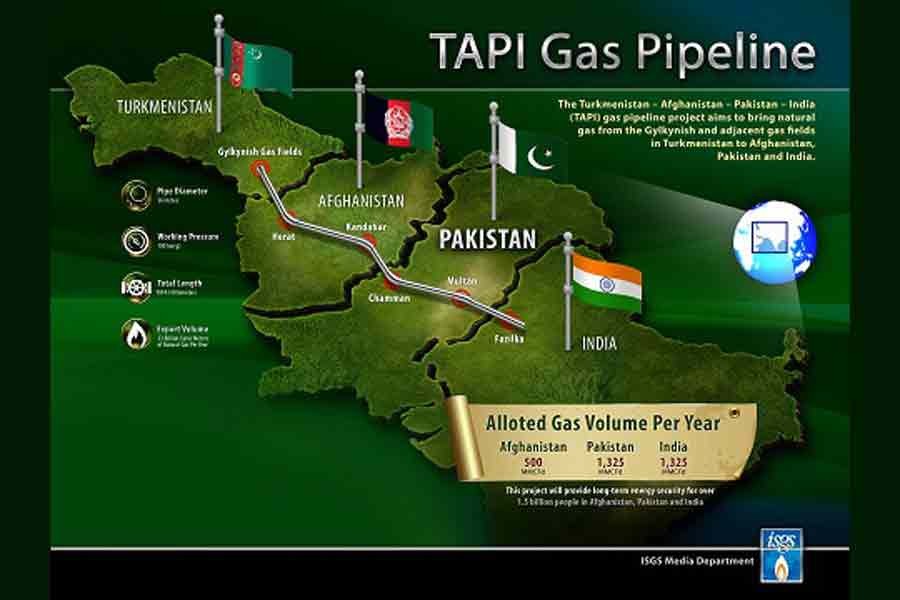

This dilemma is also facing Joe Biden. There is no guarantee that the Taliban will want to include American companies in the country's future, but in 1997 they did negotiate with the American oil company Unocal regarding the construction of a natural gas pipeline that would go from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan to Pakistan and India.

At the time, they didn't present religion as a barrier for doing business with the West in general or the U.S. in particular, just as Unocal and President George Bush did not make the improvement of human rights a condition for doing business with the Taliban. It seems that when the "shock" of the Taliban takeover fades, we'll start seeing the representatives of Western companies in their suits and ties doing business in the exorbitantly-priced hotels of Kabul.

The piece is excerpted from Haaretz (www.haartez.com)