Published :

Updated :

To modern English knowing persons, the language of the ancient heroic epic poem 'Beowulf' appears to be strange. Although written in Roman letters and containing words similar to those in English, the narrative doesn't seem to be English at all. An inquisitive reader has to turn to linguists to decipher the meanings of the language -- the earliest form of English. It is normally called Old English. 'Beowulf' was written in this English around 1,000 years ago. Students of English literature today enjoy reading the epic by 'translating' its language in modern English. Those interested in the evolution of Bangla has a similar experience.

The language of 'Charjapada', the earliest form of Bangla lyrics, sounds quite different while reciting. Their written form, especially the syntax, is, however, much different from the Bangla used today. The fact applies to almost all living languages. It doesn't require scholarly discussion to arrive at a universal conclusion. These newer forms of expression denote a trait latent in every human -- undergoing or prompting change.

Changes define life. As life goes on, humans drop their old garb and customs to embrace newer forms and expression. Languages, thought processes and customs continue to change without man being aware of them. Shifting from the intangible areas of tradition and culture, man enters the mundane spheres of life. Here also everything is meaningless without change. From the style of living as part of society and community to learning to adapt to new realities, humans in every activity of their emerge as different from their earlier selves. They also influence their surroundings; and the process goes on vice versa. Beginning with the look of an urban landscape to that in a village, man invariably finds how time keeps working wonders of sorts on the age-old human settlements.

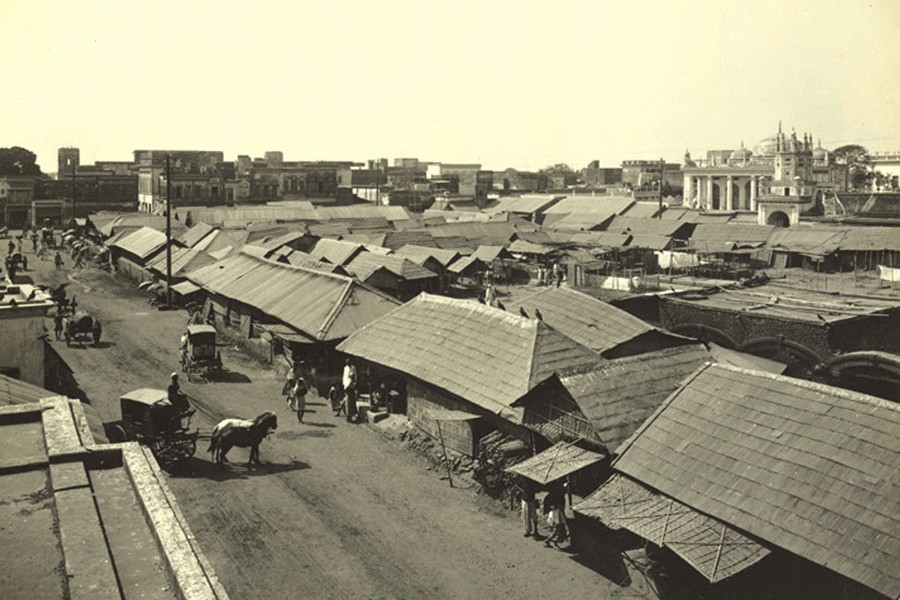

Coming to the spectacles of Dhaka now and in the past, lots of wonders appear to be in store for inquisitive youths. It might begin with the Mughal period of the historic city when pedestrians clad in dhoti- 'fatua' or lose pajama-'kurta' and, on occasions, in festive 'sherwani' were common sights. Moneyed people on horses were also usual scenes. In the British colonial period, everything concerning people's lifestyle including dresses remained almost the same. The only new addition comprised the sahibs in shirts and pants with heavy hats covering their heads. Most of them would be found astride horses. Quite often, fairy-like mem-sahibs accompanied them.

In a considerable gap of time, the 'gora' sahibs eventually came up with their original face showing their superiority as the rulers. It was an ugly development; they made it a point that they had the licence to discipline the unruly and uncivilised native Indians. However, this scenario didn't last for long. Unlike the rural scenarios in Bengal, the cityscapes in the region passed through series of socio-political transformations. The then East Bengal was no exception. In these spells of all-round change at the advent of a new era, the only legacy of the British colonial rule appeared in the form of Dhaka's urban development. It was the British city planners who had longed to see Dhaka as a scientifically built urban centre.

The now disappeared and mostly dysfunctional canals were aimed at the city's flowing out of rainwater. They stood proof to the colonial rulers' eagerness to see an ideal city in Dhaka. They built a lot of other edifices like educational institutions, court buildings, railway stations and bridges etc. As time wore on, these signs of a new time, too, began turning grey to embrace new emblems of yet another era.

The journey of changes is long. To define it aptly, it is infinite. Seeing the universal changes in operation and discarding the old practices dispassionately proves the ephemeral nature of human trends. A surprising aspect is many inanimate objects are also not free of the interventions of changes in a well placed system. Lots of people are found not prepared to accept changes. However, it doesn't mean that the persons who have experienced difficulty reading a text written in old English or Bangla want to stop evolution. It's because this resistance to change goes against the rule of nature. It goes against overall human welfare.

As warranted by the universal rule, lots of changes continue to take place in life. The city of Dhaka was once filled with ponds of different sizes. People coming to the city after a gap of several decades felt stunned at the disappearance of the ponds. Upon remaining shocked for some time, and finally coming to grips with the reality, they would accept the fact. This mental agony may be defined as the price of change. A couple of centuries ago in rural Bangladesh, villages in a row would be found devoid of human settlements. Vast rural expanses would be found veritably haunted by death. With no effective medicines yet to reach villages in those days, epidemics of cholera and small pox would wipe out thousands from villages. The radical changes brought about by cholera and small pox vaccines in the later years helped the illiterate villagers experience a new lease of life. After the countrywide cholera and small pox eradication campaigns, the most noticeable change came in the form of awareness-building among the rural folks. At least they had learnt cholera was not spread by an evil supernatural woman called Ola Devi. Nor did small pox result from a noxious whiff of air.

In a couple of decades, the Bangladesh villages became free of two deadly endemics --- the age-old cholera and small pox. Thus despite the initial jolts and confusions, changes in lifestyle appear in human life to herald many a revolution in their day-to-day life.

Apart from the medical, socio-cultural and political changes with far-reaching implications, a living society also witnesses lighter changes. They mainly involve their way of life including the spheres of using dialects, jargons and slangs. The style of dressing up or fashion continues to undergo changes. They occupy a centre-stage in the researches carried out by social observers. Even the outer views of a city or a village take newer looks through the passage of time. A common scenario in the streets of early Dhaka used to comprise horse-drawn carriages, push-carts etc. Urban male youths would be seen it 'teddy' pants, shirts and pointed shoes in the 1960s. Young women of the time also didn't lag behind, as they took to the female version of the skin-tight apparel. In a decade, the 'teddy' style of dressing gave way to the 'bell-bottom' fashion. Due to their weird look and the feeling of discomfort they gave, the 'bell-bottom' couldn't last longer. Through the passage of time, the ubiquitous cinema ticket scalpers, popularly known as 'blackers', have vanished from around the cinema theatres. So have the various types of entertainers like 'box cinemawallahs', sharp-tongued snake charmers, invariably young women, and monkey-dances.

In the last five to six decades, Dhaka has undergone series of radical transformations in its look and nature. Accepting changes gracefully is intrinsic to humans. If they do not welcome a change, they risk being called out of step with time. Eventually, these arrogant people find themselves stuck in a labyrinth.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Financial Express Google News channel.