It is passé to say, inequality is as old as civilisation but critique and attempts at resisting and alleviating it is recent. While the beginning of inequality with the rise of private property in place of communal ownership of means of production, particularly land, is well documented, the history of resistance against it and adoption of countervailing measures has only been sporadically written. However, a vast international program of international and comparative research has recently led to the publication of several individual and collective reports and studies as well as the recent development of the World Inequality Database (WID). These research and studies have shown that there has been a long- term movement over the course of history towards more equitable distribution of income and wealth and more social political equality. But this is not a peaceful, continuous and steady progress. The history is punctuated by multiple phases of regressions and social upheavals.

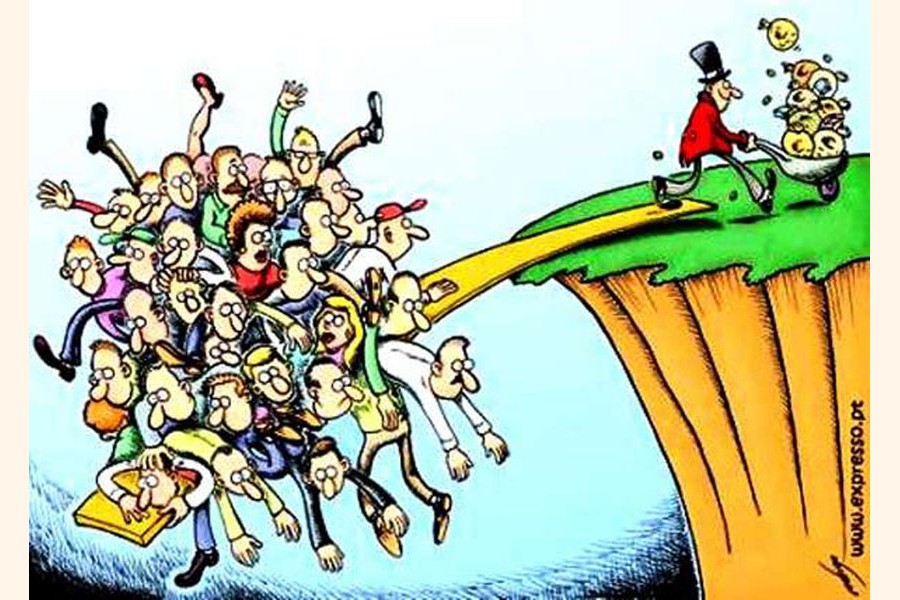

Nevertheless, at least since the end of the eighteenth century there has been a historical movement towards equality. It can be statistically proved that the world of the early 2020s is more egalitarian than that of 1950 or that of 1900 which were themselves more egalitarian than those of 1850 and 1900. But it is not the inter-temporal comparisons of inequality that matters, but rather the incidence of inequality at a particular time that hurts those at the lower end of income ladder. There is no doubt that measures to mitigate inequality can be traced to the thoughts of Plato, Rousseau, many socialist schools and Karl Marx and epochal events like French Revolution in 1789 and Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, but it was economic crises like the great depression of 1930s that triggered social welfare measures for the poor and unemployed, financed by higher tax on the rich and wealthy. While the historical 'trend' towards reduction in inequality has been uneven and incremental, events like war, pandemic, economic depressions have seen sudden and massive rise in social security measures to help the poor and the unemployed. In many countries these measures continued even after the crisis was over, even if in attenuated form. Both during the crises and afterwards it has been the government, not the private sector or philanthropies that has implemented social security measures with tax revenue, impinging on inequality of income and wealth. The rich, at whose 'cost' the welfare measures have been financed, have not relished this and have exercised their political power to water down the social safety net programs at every available opportunity after the crisis-time emergency is over. In many cases they have won, as in America and social democratic countries in Europe in recent years. Reining in inequality, therefore, has become the test of the power and willingness of political leadership. It is not enough for public policy to come to the rescue of the low income group in times of crises, it has to be its constant goal to ensure adequate income for the poor to enjoy a decent standard of living, defined by ability to have basic needs plus, a moving target at any particular point of time.

It should be made clear that inequality of income does not have to be reduced on moral grounds, but because it is a economic necessity to do so to provide basic needs goods and services to the low income earners and the unemployed, in addition to other services of governments. If this can be ensured without touching the income and wealth of the rich, taxing them at the same level as the average tax payer, no question would be asked about inequality caused by their differential income and wealth. But short of printing money a government does not have any other wherewithal than collect taxes from those who can afford. All the upbraiding against inequality and giving it a bad name, based on moral ground, misses the more compelling reasons for its reduction through taxation. In democracy no government can and should declare a crusade against inequality of income and wealth, as long as they are amassed through honest means and the functions and services of government under social contract can be ensured with the tax revenues (and income from other sources) collected equally from all income groups. But this is a fairy tale public finance, not in tune with the real world. The resources needed for proper functioning of the government, including looking after the needy, makes progressive taxation inevitable and unavoidable. This is not to punish the rich but as a matter of routine for those who have enough and to spare. If this not convincing enough of a reason, there is a second justification for taxing the rich more than others: they have earned their income and wealth in an environment of law and security provided by government for which they have to pay back. Progressive taxation on the rich, either through income or wealth tax, enables a government to carry on its functions, benefitting the rich and poor alike. Here, reduction of inequality is not the primary goal. Seen from this perspective, inequality will not be seen as a 'beast' at all. For diversity of the economic ecology, it may even appear as necessary.

Three types of taxes have been proposed for people in higher income bracket on the basis of progressivity: income tax, corporate tax and wealth tax. Of these, the progressive income tax is the oldest, having been introduced in America and Europe in the beginning of twentieth century. Before twentieth century, almost all the world's fiscal systems were regressive in nature, based on sales tax and other indirect taxes, representing a proportionately higher burden on the low income earners. The progressive income tax, introduced in the beginning of twentieth century has had a uniform history in developed countries, showing steep rise and a sharp decline in some countries. According to Piketty, the marginal tax rate applied to the highest incomes was on average 23 per cent in America from 1900 to 1932, it rose to 81 per cent from 1932 to 1980 and then fell to 39 per cent between 1980 and 2020. According to his research, in the same periods, the top rates were 30,89 and 46 per cent in the UK;26,68 and 53 in Japan ; 18,58, and 50 in Germany; and 23,60 and 57 in France (Thomas Piketty, A Brief History of Equality,2022).In Piketty's estimate progressive taxation was greatest in the middle of twentieth century, particularly in the America and the United Kingdom(UK). These figures show that in America and UK progressive income tax rose sharply and then declined significantly as the century neared the end. Only Japan, Germany and France maintained a moderate level during that end period. This speaks volume about fiscal conservatism in America and the UK and the influence of social democratic ideology in Europe. Progressive income tax has waxed and waned with the change of governments with different ideologies, liberalism and conservatism.

In his book, Piketty raises the question: could progressive taxes have been so quickly established without the shock of World War l, and without the Bolshevik regime's pressure on the elites in capitalist countries? While admitting that it is a difficult question defying an unequivocal answer, he observes: "The invention of progressive taxation must nevertheless be seen as the consequence of both a social and political movement and a long term protest movement. This process was accelerated, of course, by multiple events, (wars, revolutions, economic crises), but the relative importance of these varies greatly depending on the country." He concludes, saying that economic crisis was more compelling in adopting progressive income tax than war or revolution, at least in America, making it imperative to 'regain control of capitalism'. He laments the near disappearance of progressivity in taxation, in America and other capitalist countries, making it possible for wealthiest people to succeed in paying taxes at effective rates lower than those paid by the middle and the lower income classes. The case with progressive taxes in countries like Bangladesh does not show the same trajectory of rise and fall but its major bane has been evasion of payment of taxes, often in collusion with tax collectors.

As regards other forms of taxation on the rich, the corporate tax in capitalist countries show sharp fluctuations between high and low, depending on whether the liberal social-democrats or the conservatives are in power. For instance, in America the corporate income tax was whittled down by President Trump, from 40 per cent to 25 per cent, when the conservatives came to power. Very recently, the OECD countries reached an agreement to impose corporate tax at a rate not lower than 15 per cent, implying that developed countries resort to protectionist measures, favouring their flagship companies with lower tax rates. In his book, Piketty has lamented the fact that in capitalist countries large companies succeed in paying at a tax rate lower than that of small and medium- sized companies.

Though the idea of slapping wealth tax on the rich has been toyed with and proposed by economists like Piketty (Capital in the Twenty-First century, 2014), as of now no country has used it to raise tax revenue or to reduce inequality of income. In the event, it has remained a hobby horse to play around by policy makers.

To sum up, inequality should be reduced not because it is morally repugnant but because of the economic necessity of raising revenue income through progressive taxation so that governments can conduct their normal and welfare functions. There is nothing ideological about it either.

[Two relevant articles by the same author: Inequality: Looking at the beast, conceptually (P-4, January 01, 2023, FE)

Inequality: looking at the 'beast', empirically (P-4, January 13, 2023, FE)]