Scientists say they have observed a signature on the sky from the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

They did it with the aid of a small radio telescope in the Australian outback that was tuned to detect the earliest ever evidence for hydrogen.

This hydrogen was in a state that could only be explained if it had been touched by the intense light of stars.

The team puts the time of this interaction at a mere 180 million years after the Big Bang.

Given that the cosmos is roughly 13.8 billion years old, it means the first stars lit up a full nine billion years before even our own Sun flickered into life.

Dr Judd Bowman of Arizona State University, US, is the lead author on the scholarly paper describing the observation in the journal Nature.

He told that the discovery's great significance meant his group had to be absolutely sure no mistakes were made.

"We first started seeing signs in our data back in late 2015. And we've really spent the last couple of years trying to think of all sorts of possible alternative explanations, and then rule them out one by one," he said.

"This is the first time any team has been able to present evidence for the detection of this signal and hopefully it will go down as a milestone for this type of astrophysical observation."

For decades, scientists have sought evidence for the very first population of stars, says a BBC report.

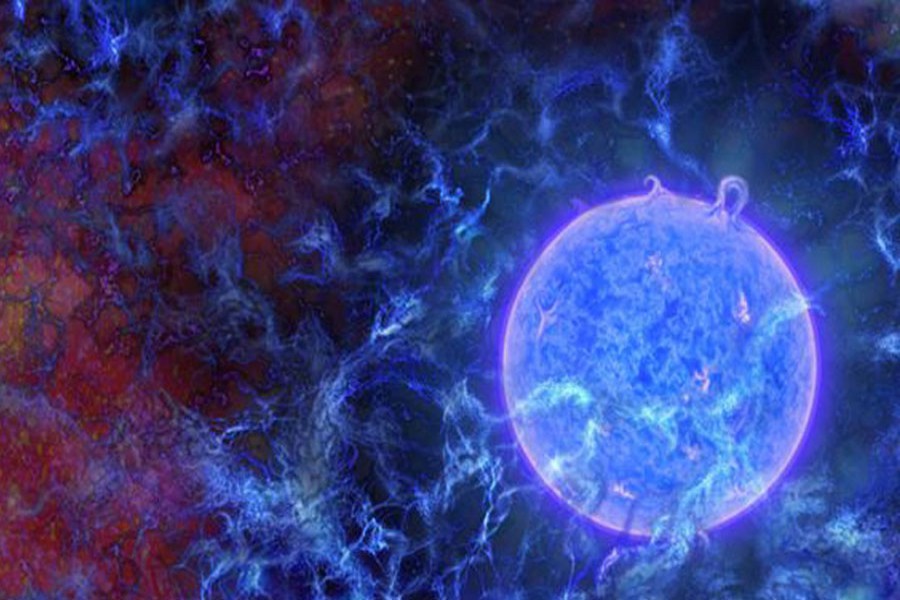

Theory says they would have grown out of the cold hydrogen gas that filled the Universe following the Big Bang. They were very probably unwieldy giants that burned brilliant but brief lives, before then exploding and seeding the Universe with all the chemical elements that make life possible.

People cannot see these ancient behemoths directly with current technology, but they can, say astronomers, capture an indirect proof of their activity.

Their ultraviolet light should have altered the great clouds of hydrogen surrounding them, exciting the gas into a state that made it absorb background radiation at a very specific radio frequency of 1.4 gigahertz.

The challenge for the table top-sized telescope at the Murchison observatory in Western Australia was to try to pick out this signal in the sea of radio noise coming from the sky.

Part of the issue was knowing where exactly to search on the spectrum, given that the expansion of the Universe over the eons would have stretched the signal to much lower frequencies.

But the team eventually found it in the region of 78 megahertz.

'New window'

Of significant interest is the strength of the signal which is well above expectation.

This suggests, say commentators, that the hydrogen gas was a lot colder than previously supposed.

And Prof Karl Glazebrook from Swinburne University of Technology, Australia, said astronomers worldwide would now be holding their breath until the result was confirmed by an independent experiment.

"If it is, then this will open the door to a new window on the early Universe and potentially a new understanding of the nature of dark matter," he explained.