Images of some of the more incredible of moments in history all too often shape, indeed define our sense of history. It is experience that is both individual and collective. In an era --- and we mean the twenty-first century we happen to inhabit in these present times --- when great leadership is conspicuous by its absence, we need to travel back to some of those times, to the men and women whose lofty spirit and profound understanding of the world around them deepened our comprehension of the workings of history.

There is the image of a kneeling Willy Brandt in Warsaw in 1970. For the very first time since the defeat of Nazism, here was a German leader whose heart told him he needed to express contrition on behalf of an entire nation. In Warsaw, it was a sudden call of the heart which told him to kneel. In that kneeling, he reached out to the world, as he would reach out to it with his Ostpolitik. And Ostpolitik was the beginning of a thaw in the hard ice of the Cold War.

In Lahore, in February 1966 and February 1974, it was history which Bangabandhu made and then solidified, convincing his people and the world that he meant business in his pursuit of politics. In 1966, in the very city that had set the movement for Pakistan going, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman informed the world that change, through his Six Points, was on the way. In 1974, as the Bangladesh flag fluttered and the Pakistan army band played Amar Shonar Bangla at Lahore airport, Bangabandhu stood triumphant on the dais. He had transformed history to his specifications.

Charles de Gaulle, a keen student of history, knew of the impact historical decisions could have on nations and so turn into historic images of a world in transformative mode. When France fell to Hitler's forces in 1940, de Gaulle inspired his people with doses of necessary optimism from his base in London. France, he said, had lost a battle. She had not lost the war. It was thus that de Gaulle pushed Petain and Laval into the shadows and would move on to tell Frenchmen that grandeur was theirs, that destiny was theirs to shape.

In the twentieth century, handshakes became determinants of historical evolution. In February 1972, conscious of the disdain with which John Foster Dulles had walked away from Zhou En-lai in Geneva in 1954 rather than take his hand in politeness if not friendship, Richard Nixon came down the steps of his presidential aircraft in Beijing, his hand extended to a waiting Zhou. The world changed in those few moments and Nixon and Zhou turned a new page.

Similar was the moment in Jerusalem on a November night in 1977 when Anwar Sadat, four years after the Yom Kippur War, held out his hand to Menachem Begin and so initiated a dramatic change in politics in the Middle East. Sadat, an Egyptian soldier committed to the destruction of Israel, and Begin, a former Zionist radical whose sense of history was circumscribed by notions of Judea and Samaria, gave diplomacy a new fillip through that handshake. The needles of history moved.

Indira Gandhi's moment in history shone bright on the afternoon of the day her army, with Bangladesh's Mukti Bahini, presided over the surrender of Pakistan's occupation forces in Dhaka. On 16 December 1971, she proclaimed before India's parliament, "Dhaka is now the free capital of a free country." She had defeated a rapacious army; and she had supervised the emergence of a new nation. Atal Behari Vajpayee, in opposition and future prime minister, acclaimed her as Durga. She deserved the honour, and more.

In April 1971, history was accorded a new dimension by Tajuddin Ahmad through his announcement of the formation of the very first Bengali government for a soon to be independent Bangladesh. In his intellectual analysis of history, Tajuddin was acutely conscious of the idea that exile would need to be reconfigured into concrete action for his suffering country. The inauguration of the Mujibnagar government, the shaping of guerrilla strategy and the formulation of policy for a fledgling country were the foundations on which Tajuddin Ahmad rebuilt history.

For Nikita Khrushchev, his history moment came in 1956 when at the congress of the Soviet Communist Party he roundly denounced the dead Joseph Stalin, thereby signalling an end to the silence that had prevailed over the purges emasculating politics since the 1930s. Khrushchev's speech was the beginning of tentative liberalism in Moscow, though it was much marred by the military intervention in Hungary in the same year and the later intimidation of Boris Pasternak over the latter's Nobel Prize for literature, compelling the writer to decline the award.

In Egypt, history was jolted into a newer and assertive form when Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal. Arab nationalism was in the ascendant, strengthened by the folly of the French, British and Israeli governments in believing they could compel the Egyptian leader into surrender. If in 1952 the coup against King Farouk symbolized the overthrow of feudalism, 1956 was the point that paved the path to global prominence for Nasser. He gave Arabs a new sense of identity, one that would be emulated by others in the Middle East down the years.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy set history on a new course in 1961 through his ringing call for a man to be sent to the moon and have him return to Earth within the decade. Kennedy did not live to see his dream fulfilled, but when the astronauts of Apollo-11 landed on the lunar surface in July 1969 and returned safely home, science redefined life on a global scale. The moon programme was an essential component of Kennedy's New Frontier, an important plank of his legacy.

Nelson Mandela gave a new interpretation to history with South Africa transcending to a Rainbow Nation in the mid-1990s. The long years in prison did not radicalize him but saw him mellow into a voice of reason and hope. The last statesman of the twentieth century, Mandela was light unto the world, with his wisdom, with his inclusive politics.

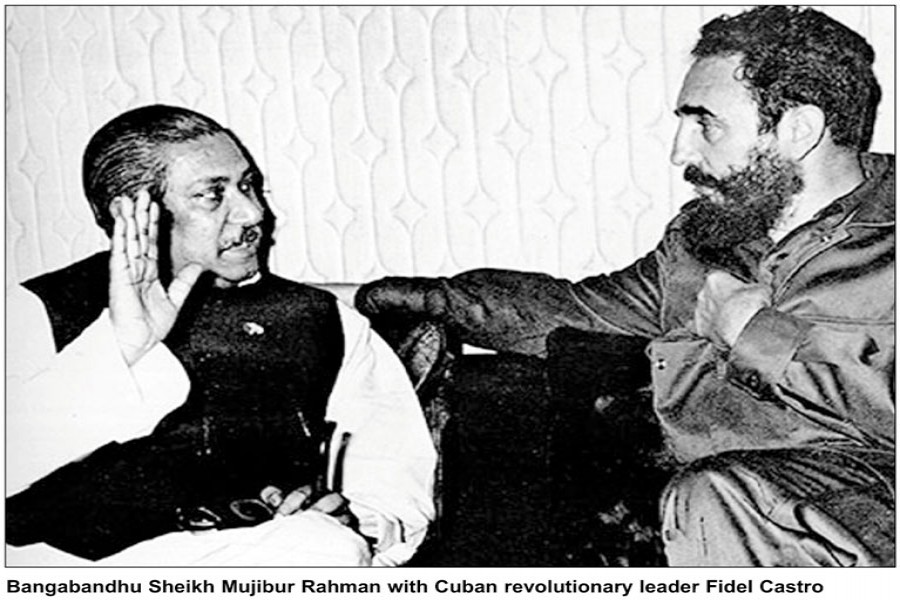

When Fidel Castro marched into Havana and put Fulgencio Batista to flight in 1959, he inaugurated a new era, one of socialist equality, for all Cubans and so inspired people everywhere with hope for the future. Salvador Allende informed the world in 1970 that democracy could become expansive through the election of socialists to power. Three years later, gun in hand and helmet on his head in Santiago, he defied the coup against his government, perishing in the process. That was his history.

History gleams. Shining cities on the hills rise through such leadership, in such demonstrations of vision.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a senior journalist and writer.