Developing nations should withdraw from ISDS, argue experts

Little headway in meaningful reforms to global investment arbitration regime

FE ONLINE REPORT | Thursday, 16 September 2021

A number of international civil society members and experts have found that meaningful reforms to the international investment arbitration regime are far away despite making a thorough review initiative.

They mentioned that the Working Group III (WGIII) of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) has spent four years reviewing the international investment agreements, and specifically investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), with little progress.

In this context, some of them argued that the developing nations should withdraw from the ISDS process or investment treaties as soon as possible.

Having around less than one year in hand to complete the review, a new paper argued that the review “appears to be a long way from delivering meaningful reforms to the investment arbitration regime.”

“In the meantime, ISDS continues to provide foreign investors with an exclusive mechanism to directly sue host states and challenge governmental action, including non-discriminatory regulations,” added the paper.

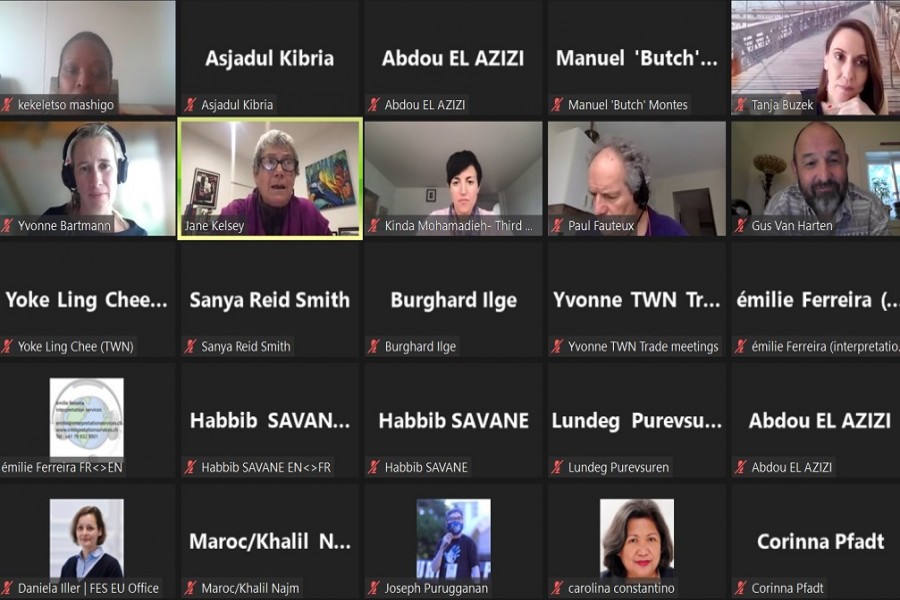

The paper titled ‘UNCITRAL Fiddles While Countries Burn’ is formally launched at a virtual meeting today (Thursday afternoon in Bangladesh time).

Jane Kelsey, professor of faculty of law, University of Auckland, New Zealand and Kinda Mohamadieh, legal advisor and senior researcher of Third World Network (TWN) jointly prepared the paper.

Moderated by Yvonne Bartmann, senior program officer, FES Geneva office, a panel of commentators including developing country delegates, and representatives from civil society and academia, also shared their views at the event.

The paper analysed the work of UNCITRAL WGIII from the development perspective and identifies that several factors are behind the failure of WGIII to make effective advances towards urgently required reforms. These include: narrow interpretation of the UNCITRAL mandate to cover a limited set of procedural issues, the prescriptive agendas limiting many concerns raised by developing countries, and the procedures adopted before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The authors argued that effective consideration of the developmental implications of ISDS requires freeing the mandate given to WGIII from the narrow interpretation adopted to date and taking a serious look at alternatives to arbitration as means to settle investment disputes.

They also mentioned that during the four years of deliberations in the UNCITRAL Working Group, the pattern of ISDS disputes has remained the same.

The paper also added that among some 71 substantive arbitral decisions that UNCTAD identified in 2019, almost half were still secret.

“While investment tribunals appeared to be more aware of the potential for backlash as they went about their business, the published decisions still displayed divergent interpretations by arbitrators and tribunals on certain key issues,” it said adding that during the period, amounts awarded to the investors ranged from $7.9 million against Hungary to $5.9 billion against Pakistan and $8.4 billion against financially crippled Venezuela.

It is to be noted that in July 2017, UNCITRAL entrusted its Working Group III with a mandate to work on the ‘possible reform of ISDS against the background of its global reach and its experience with the negotiation of legal instruments in the field of international dispute settlement.’

Given the frustrations with the UNCITRAL process, some participants at the discussion argued that there is a small chance that UNCITRAL would engage meaningfully with the reform of the whole ISDS system. A few of them also stressed focussing the energies on getting states to unilaterally withdraw from ISDS as Pakistan did recently.

In fact, added other discussants, a number of countries have already been withdrawing from their bilateral investment treaties including Bolivia, Ecuador, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Venezuela.

In this regard, Gus Van Harten mentioned that if there is a bilateral investment treaty, withdrawal is possible unless the other party agrees to remove ISDS promptly. In the case of a trade agreement, it is more difficult to withdraw.

Harten, a professor of Administrative Law at York University's Osgoode Hall, also added that Canada and the US recently agreed to remove ISDS from NAFTA.

He also said that some states have lack the will or capacity or space to withdraw, but unfortunately for them, the alternatives are far worse than withdrawal.

The authors of the paper, who also intervened in the discussion, argued that a serious look at alternatives to arbitration as means to settle investment disputes is necessary now.