It was a crisp, biting winter afternoon when I set out on my way home, my left hand on the handlebar of the bicycle, my right hand holding a huge portrait, in colour, of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. I kept the portrait open, my intention being for everyone on the streets I bicycled through to have a glimpse of the man who had led his party to a convincing victory at the general election a day earlier. It was December 8 , 1970 and the place was Quetta, Baluchistan. I had just been to the provincial office of the Awami League, where a beaming Mir Mohammad Khan Raisani, chief of the Baluchistan Awami League, had given me the portrait.

In the event, it took me a pretty long time to reach home, for at nearly every spot on the way I was stopped by people, young and middle-aged and elderly, who wished to have a closer look at Bangabandhu. It was that particular moment in my life when I felt mighty proud of being a Bengali. Among the elderly men who made me stop were those who told one another that it was a happy augury Sheikh Mujib would soon be Pakistan's Prime Minister. Some asked me about Bangabandhu's age. There were many who asked me where I was from. When I told them --- and they were Pathans, Baluchis, Punjabis, Sindhis and Urdu-speaking --- that I was a Bengali, the smiles on their faces came on bright and sincere.

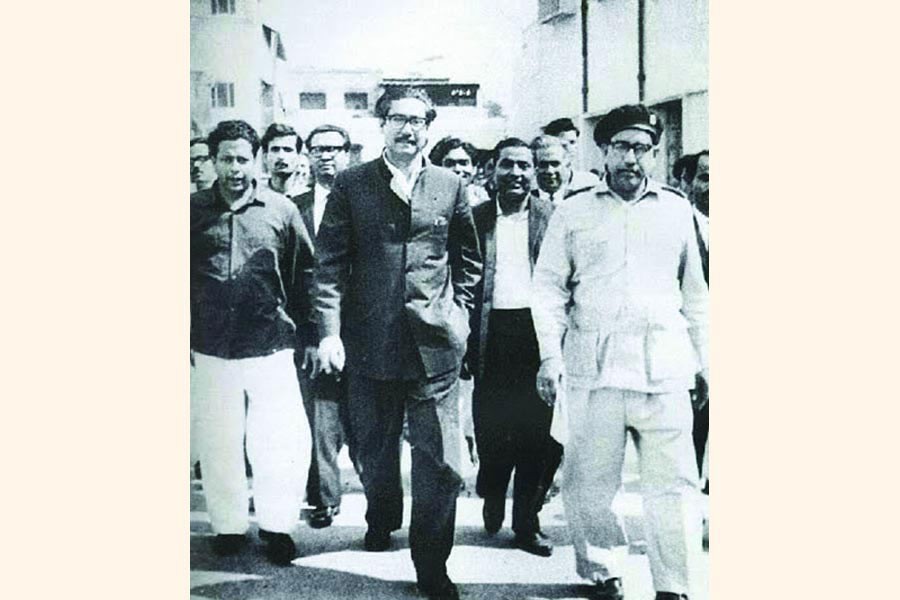

The wind was bitter as I finally reached home, showed the portrait to my parents and siblings and had it placed prominently on the wall. I was yet dizzy from the thought that Bangabandhu had finally triumphed against all opposition and all intrigue. Only six months earlier, it had been my good fortune to meet him, have dinner with him on an evening draped in the scent of roses and sunflowers. He was in Quetta on a campaign swing through West Pakistan and Raisani had been generous enough, because I needed a chance to get Bangabandhu's autograph, to hand me an invitation card to a dinner that would be attended by prominent personalities of Baluchistan. I was yet in school, but it felt good to be there among that group of illustrious men.

It was a beautiful, breezy summer evening when Bangabandhu, rather than taking my outstretched hand, placed his huge hands on my cheeks and pulled them in clear affection. He wanted to know about my school, about my parents. And then came the question, in Bengali: "Deshe jaabi na?" Seeing me fumbling for an answer, he modified the question: "Bangladesh-e jaabi na?" It was wonderful hearing the future Father of the Nation pronounce 'Bangladesh'. The rest of the evening was spent sitting beside Bangabandhu as he sat conversing with the guests, at one point reprimanding Yahya Bakhtiar when the latter thought the Six Points would destroy Pakistan. Bangabandhu and Abdus Samad Achakzai embraced, joking about the times they had both had long spells in prison per courtesy of the Ayub regime. After dinner, I held out my autograph book to Bangabandhu. This is what he wrote there: 'Joi Bangla!' before affixing his signature. I went back home thrilled to no end. It was a night brilliant in starlight.

There are all the images I have of Bangabandhu, at a pretty personal level. The very first time I heard of him was when my father educated me on his politics in early 1968 as the Agartala Case made the headlines in the newspapers.

Sheikh Shaheb, as my father put it, was a true leader of the Bengalis. Not until February 1969, as political upheaval in both wings of Pakistan rocked the regime of Field Marshal Ayub Khan, did I see Bangabandhu's picture for the first time. He wore large, thick spectacles as he shared space with other political leaders invited to the round table conference proposed by the regime. It was on the front page of the Pakistan Times. And then came that moment when, the Agartala Case withdrawn, Bangabandhu was a free man. The front page of Dawn carried his picture, the leader holding his daughter Sheikh Hasina in a warm paternal hug. As a student of class eight, I had followed every bit of news relating to the trial in the Agartala Case as it appeared with regularity in Dawn. And now, in class nine, I was certain Bangabandhu was on his way to greater heights of leadership.

The images flash through the mind --- of me being checked at Karachi airport in July 1971 every time I walked out to have some fresh air before boarding a PIA flight to Dhaka with my family. Bangabandhu was a prisoner somewhere in West Pakistan, Bengalis were being murdered by the Pakistan army in occupied Bangladesh and in my pocket was a pencil sketch I had made of Bangabandhu soon after the election. Of course I did not know, not until we reached Dhaka on a very rainy evening, that the sketch was there; and airport security had not thought of putting their hands into that inside pocket of my blazer. I can only imagine the consequences if the sketch had been discovered by those men at Karachi airport. But on that day, it was the image, dating back to April, of Bangabandhu, a prisoner sitting on a sofa and flanked by two policemen at that airport which worked in my mind. We did not know if he was alive. We did not know where he was.

Ah, it is always the images of Bangabandhu, in those years when he reconfigured our history, that remain indelible imprints in my memory. That tumultuous afternoon at Tejgaon airport when he stood on the truck after his triumphal return home on 10 January 1972 --- tired yet alert, running his hand through his hair, looking intently at the cheering crowd --- is part of our legacy. I stood there, in front of the truck before it began to move, looking at him. Was he looking at me? But then, he was looking at everybody, for it was an entire nation embodied by that welcoming crowd around him. I went round to the back of the truck, managed to hang on to it even though one of my feet scraped the road, until it reached Shahbagh. In that million-strong crowd, I sat in the middle of the road between Suhrawardy Udyan and Ramna Park, to hear the Father of the Nation speak to us of his travails in prison, to give us a sense of direction for the future. Then all of us went home. Bangabandhu was back home among us and Bangladesh was on its way to the future.

On an April afternoon in 1972, worried about my academic future, I walked to Ganobhaban. Perhaps Bangabandhu could help? It was a time when a day of the week was set aside for citizens to place their grievances before the Prime Minister. The office staff at the reception sent my note, along with those of others, to Bangabandhu. Within minutes he emerged from his office, my note in his hand, demanding to know who had written it. At my feeble reply, more in trepidation than in confidence, that it was I, he surprised me by wanting to know when I had come back from Quetta. And were my family members safe and well? He remembered! It was a schoolboy he had seen nearly two years earlier and he remembered! I jumped for joy and skipped and hopped all the way home to Malibagh, happy that Bangabandhu had assured me my education was safe, that I should carry on with preparations for my Senior Cambridge examinations.

Yes, the images come alive --- of the endless evenings I stood, in steamy weather and monsoon rain, outside the gates of the old Ganobhaban for a glimpse of Bangabandhu as he went back home to Dhanmondi. I waved at him and he waved back. And then one day he advised me not to stand there every day but focus on my studies at home. I was then a student of Notre Dame College. The last time I saw him was on Independence Day in 1975, as he addressed the crowd at Suhrawardy Udyan.

On a day in August 1996, in the quiet lunar beauty of the night, I sat for long hours beside Bangabandhu's grave --- in sadness and in deep homage to him. The grass and the flowers on the grave swayed in the breeze.

There are all the monsoon evenings when the rain beats down on my village, when the winds play in the palm trees. And I watch the rain mingle with the waters of the pond. And I hear the songs of the poet of politics that was Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, beyond space, beyond time.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is a senior journalist and writer.